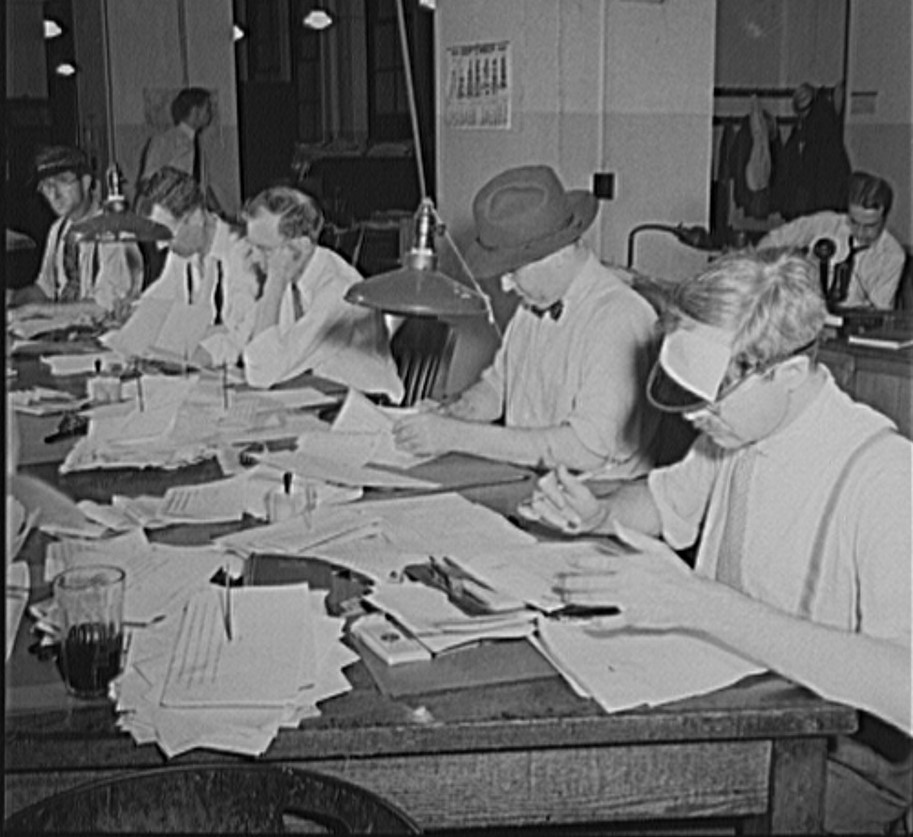

Bad editing is torment. Office workers know what I am saying. After unclear initial direction, a document goes around and around, everyone making petty and arbitrary changes, and then changes to the changes, and sometimes people make changes to their own previous changes. It only stops with the deadline, when the document is different but likely no better than when it started.

That’s not how professionals do it. Editing done correctly is efficient and purposeful.

In my last newsletter, I explained the fundamental rule supporting this process: decisions start big and get smaller as you go on. As in a negotiation, you don’t go back and change the basic deal when you are dotting the last i.

First comes the acquisition or developmental editor. In newsrooms, this is the assignment editor. Or just ‘the editor.’ This person’s job is to help define the project and give big-picture feedback on how the piece is coming together.

Next comes the line editor, who is usually the same person as the acquisition editor in book publishing. The line editor marks up the text for the writer to revise, concentrating on meaning, organization, tone, accuracy, length, and the quality of the writing. The writer responds to the mark-up and the two eventually reach agreement. (Academic publishing also includes peer review and often board approval.)

Now it is down to details. The content, tone, and overall function of the piece are set.

The copy editor’s narrow mandate is to correct grammar, spelling, and conventions, to catch errors, avoid repeated words, and suggest minor improvements in keeping with the already established tone.

In book publishing, the author gets to review the CE’s work and can revert changes with a ‘stet.’ In newsrooms, the copy editor is the last set of eyes, sending the piece to press or posting it online.

Books also go through proof reading for little mistakes that might have slipped through.

This stepwise editing process works efficiently because each professional does only his or her own job to advance the text to the next level of doneness. In offices without writing professionals, texts often don’t progress in the same way. People change whatever they want whenever they want, with those of higher authority feeling especially empowered.

Sometimes they edit according to passing moods. The surest sign of an amateur editor is a text with heavy marks on some pages and hardly any on others. The main thing such an edit shows is the editor’s frame of mind from moment to moment—focused or distracted, ornery or entertained.

Half the time with these folks, there is no clue as to why they made an edit. That ‘why’ should be obvious. An editor must have a reason for every change—and ‘I like it better this way’ doesn’t count.

Skilled professionals edit based on the big decisions made at the beginning. Each change contributes to that logic. When the process is right, every word finds its place and fits its purpose.

If you enjoy my newsletter, please share it.