It was a weird feeling to have my former boss and old friend portrayed on television in an eerily perfect copy of his real look and mannerisms. Even the conference room where we used to meet was faithfully reproduced on the ABC series, “Alaska Daily.”

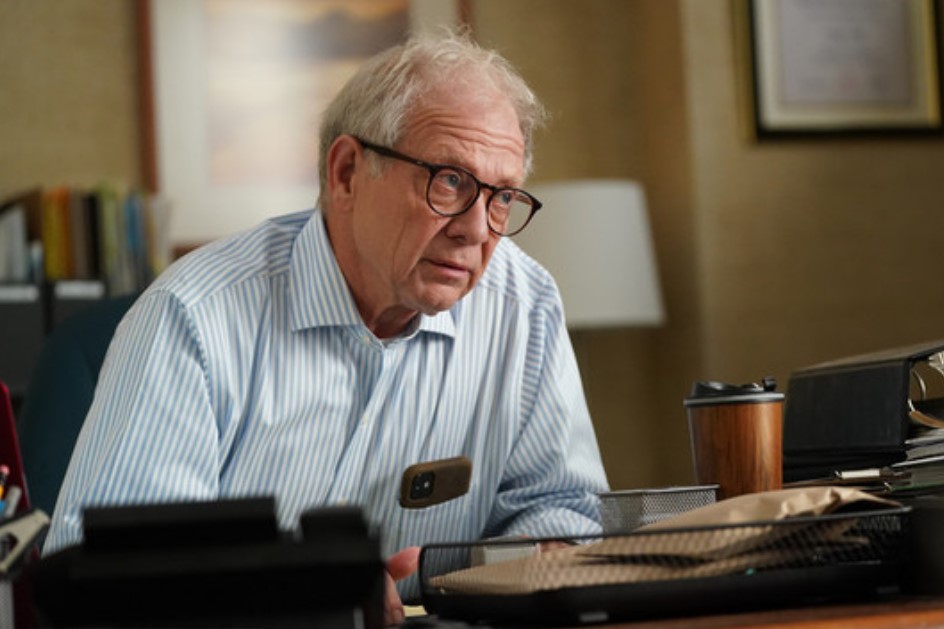

Anchorage Daily News editor David Hulen is far from famous. So why would the show give us actor Jeff Perry, with the same grey hair and glasses, the same way of holding his shoulders, even the same less-than-notable wardrobe?

The answer, I think, goes to a truth that holds in writing as well as film. Details make it feel real.

ABC based the show, starring Hilary Swank, on the News after the paper won its third Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, for its extraordinary series on rural Alaska justice. Hulen led that work as editor (and was a reporter on Pulitzer number two in the 1990s). During filming, he was a consultant to make sure the show got the details right.

In non-fiction and memoir, the details must be true. In fiction, as on the ABC series, they can be made up. But it is far easier to render evocative details from reality than from imagination.

What am I talking about?

In a production still from the show, Perry is shown with his smart phone in the breast pocket of his button-down shirt as he leans into a conversation. That detail silently tells you about the information demands of his job, and it tells you about his age and his generation.

I’ve found that when I insert innocuous but telling details in non-fiction text for clients, they will often cross out those seemingly insignificant facts—about a wilted bouquet, a harmless secret, or the yarn of a sweater.

The details make the story more intimate, even if they reveal nothing of substance. And intimacy can be scary, even if we can’t express what exactly we’re afraid of.

This is one reason why personal writing by beginners can feel flat and dimensionless.

Specific, tactile details give the imagination material to fully populate a scene with images and tensions we may not even be consciously aware of. Rendering details for readers invites them into that space.

If you’re not sure you really want them in that personal place, you may not be ready to write.

For the show, actor Perry followed editor Hulen on the job, watched how he moved and talked, and even questioned him about where he shopped for clothes (Costco, like a shocking proportion of Anchorage residents).

When I watched the show, sitting in our study in New Jersey, I felt displaced into a strange mirror reality as I saw my old friend and colleague in our old newsroom, but saying and doing things I knew never happened.

For millions of other viewers, those details were unfamiliar. They had never attended an editorial meeting in our little conference room. But the details felt real, because they were.

If you enjoy my newsletter, please share it.