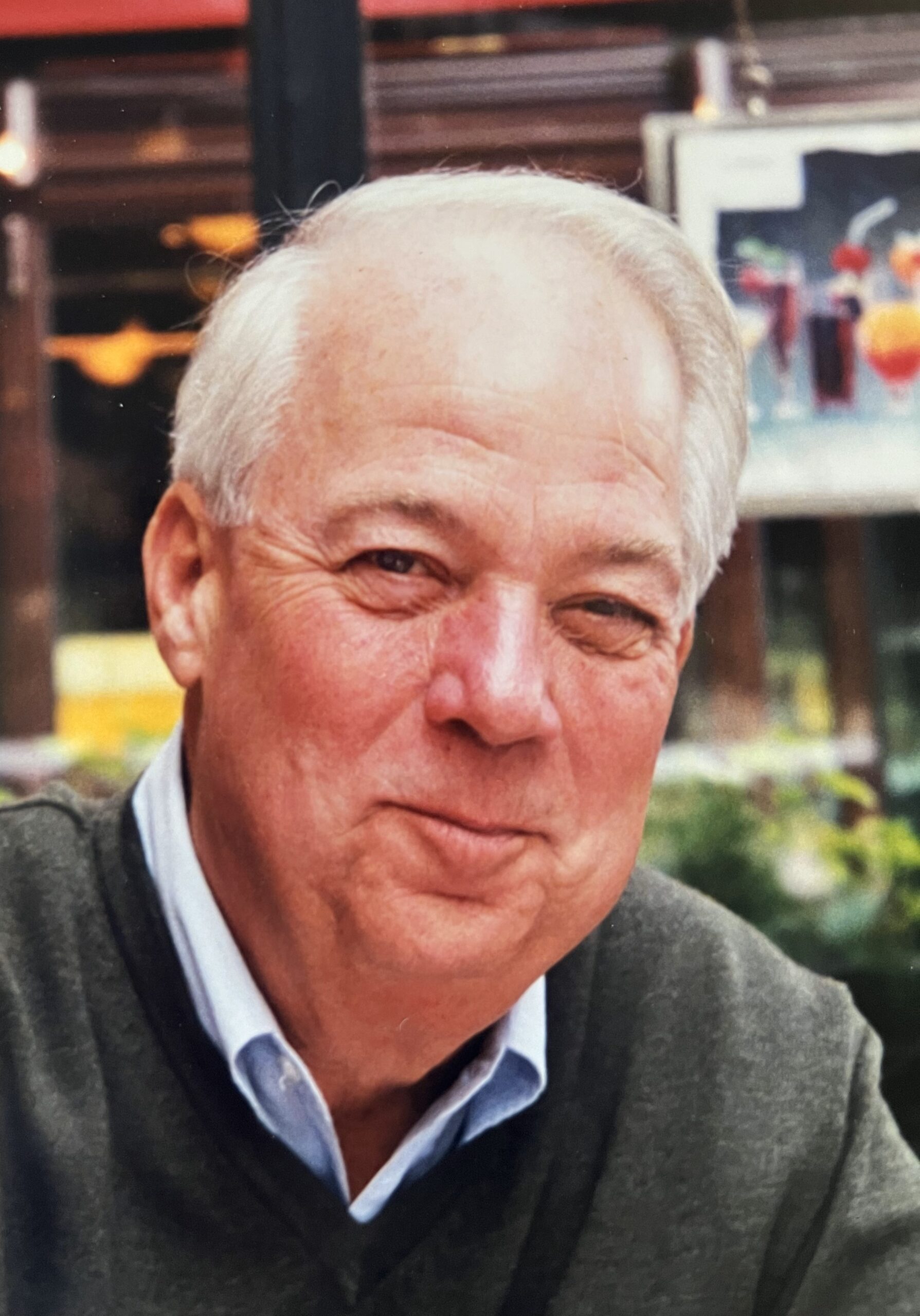

The death two weeks ago of my father-in-law, Mark Rowland, got me thinking about where writing talent comes from.

He was a respected judge, a pilot, and a legendary outdoorsman, and he crafted exquisite letters, written with a fountain pen on fine stationary, using elegant prose that despite its perfection also conveyed powerful emotions, connection, sympathy, humor, and life.

For all his stature and skill, however, Mark was known best for his conversation and his laughter. He enjoyed people and entertaining them with stories.

That, I think, is where writing talent comes from

We’re accustomed to picturing writers according to a Hollywood stereotype, and lots of writing hobbyists want to look like that, and are happy to suffer accordingly. MFA programs can turn out writers who craft perfect paragraphs that no one wants to read—and I think that’s a major reason literary fiction has declined in fifty years from the mainstream to a small niche.

The great American writers of the twentieth century came instead from storytelling traditions (and not so much from Waspy and buttoned-up Ivy League environs).

Southern writers such as William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Conner, Walker Percy, and many others, came from a culture where people sat on the porch at night and talked for entertainment.

Jewish writers such as Phillip Roth, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and many others, came from a deep tradition of language and story.

(I’m only mentioning a few of my favorites, of course.)

Mark Rowland spent most of his life in Alaska, where a few rural people still have the cultural practice of visiting. You bring some fish, some berries, or whatever you have, and you sit around the table telling stories. It can go on for hours.

Visits to his house in Seldovia were story marathons. We would sit at his table overlooking Kachemak Bay and tell stories and laugh. And Mark was even better at laughing at his visitors’ stories than his own.

It’s called ‘the gift of gab,’ but, like most valuable skills, it is more learned than inherited. Yes, a strong storyteller needs some natural facility with language, but empathy and good listening are equally important.

A good storyteller knows how the story will land in the listener’s ear.

In conversation around Mark’s table, folks heard which stories hit home, and why, and we each got immediate feedback about our own laugh-lines. Those after-dinner exchanges were like musicians’ jam sessions, taking turns with stories and punchlines rather than guitar riffs.

But I wouldn’t call those conversations practice, because I think a wonderful dinner party or afternoon spent over coffee is the main event in itself. The skills learned transfer to writing, but the story is the essential thing.

Looking back on life, writers end up with a shelf of books. But books only matter as long as someone reads them. A well-told story, shared with cheer, and passed on by friends and descendants—that is an equal form of immortality.

If you enjoy my newsletter, please share it.