Among the great (and some hilariously awful) editors I have worked with over the decades, Rebecca Saletan was among the best. From her I learned how I should work with writers.

An audacious move got my first book accepted and assigned to Becky at the most prestigious and storied independent publisher still around at the at time.

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux’s little entryway on Union Square was plastered with Nobel prizes won by its authors, including Solzhenitsyn, Singer, and T.S. Eliot. I sent in my proposal from my basement in Anchorage, Alaska.

My late grandfather, Robert Wohlforth, had worked many years at the firm, hired by its founder, Roger Strauss, after being blacklisted during Joseph McCarthy’s red scare.

Strauss attended Grandpa’s funeral in 1997. Shaking my hand in the church vestibule, he suggested I send him my writing. Four years later, I sent him a proposal about Iñupiaq whalers in the Arctic struggling with climate change. He bought the idea and assigned it to Saletan.

I imagine she would have been skeptical about this project, although she was never less than warm and encouraging. Who was this kid?

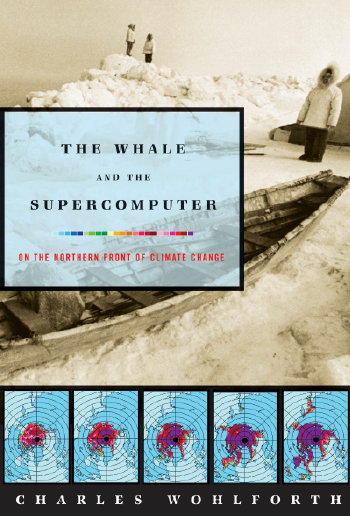

The book, The Whale and the Supercomputer: On the Northern Front of Climate Change, was unconventional in many ways. Besides being way ahead of reader awareness—I often heard, “Don’t Eskimos want the weather to be warmer?”—I chose a unique way to structure the story.

I wanted the reader to feel as the hunter does on the sea ice, slowly absorbing evidence to viscerally perceive the world changing. I would do none of the things English teachers insist upon—setting up the theme, arguments in order, wrapping it up in a bow.

After an intense year I sent Saletan the manuscript. Her initial reaction was predictably about making the story line clearer, guiding the reader through the material, reorganizing.

But then she said the most important thing.

Becky said her policy was to read a book once without marking it up so she could really understand it before editing. She would let it sit and think about it. In other words, she would respect the author.

She didn’t get back to me again for a long time. When she did, she left the structure the same. Her edits were thoughtful, limited, and all in line with making better the unconventional thing I had been trying to do, not changing it.

The book won many awards and is still in print, twenty years later.

Saletan helped make me as an editor, too. I seek to deeply understand an author’s intent before I change a word.

Like a doctor, diagnose before you treat. That’s especially important when the writing is bad, because the author’s intent may be unclear.

Such careful editing is rare these days, as publishers face tough economic pressures. But I try to pay forward the gift Becky Saletan gave me—respecting the author as she did me, a young nobody from Alaska.

If you enjoy my newsletter, please share it.