In 1934, my grandmother, Mildred Wohlforth (pen name Mildred Gilman), went to Germany to interview Hitler on assignment with the New Yorker.

After she confronted Hermann Goring with her investigative findings about the concentration camps and the status of Jews, the interview with Hitler was cancelled and she was followed by Gestapo agents. Her life was in danger. At one point she had to eat her notes to protect her sources.

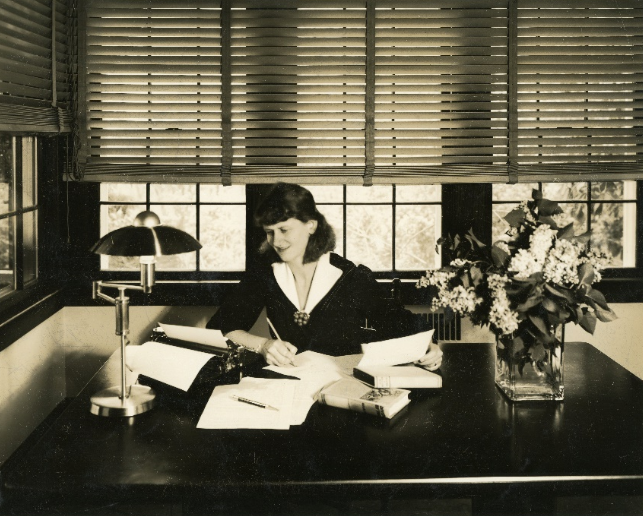

She made it home to Connecticut and her two-year-old son—my father—and wrote about the adventure, as she wrote about everything.

Grandma and I loved sharing stories about being a reporter, when I was a young one and she was reaching back to her amazing exploits in the 1920s and ‘30s. But it wasn’t until after her death in 1994 that I really got to know her.

Of course I had known her as a grandson does. I had known the eccentric old lady she had become, something of a caricature of herself that she probably put on—she had a great sense of humor and cultivated her public image, even after her public was only the family and neighborhood friends.

But after she died, I read all her novels, even the very personal, barely disguised autobiographical novels she wrote as a young woman.

I learned about how a girl from Grand Rapids, Michigan, came to New York, got married, and had a child, who was my father’s much older half-brother. And how she found her way, with magnificent talent, into a famous literary crowd with H.L. Mencken, Dorothy Parker, Heywood Broun, and many others.

I learned of how she got back late to pick up her son from daycare, the trauma for him, the deep guilt for her. She had been at an elite literary gathering, getting her big break. And of sitting at home in a tiny apartment with a husband who didn’t understand.

Perhaps having an affair. Certainly getting divorced. More deep guilt as her second husband, my grandfather, struggled to relate to her son. And as the son began to manifest emotional and mental health problems, which she blamed on herself.

I felt all this with my grandmother, when she was a girl, a young mother, a writer, a success—and I felt her torment. I felt like I lived it. Those novels put me inside her.

That’s what it means to be a powerful writer. Grandma has been dead for thirty years, but I have her novels right here. As I’ve grown, since her death, I’ve gotten to know her better every year. The experiences I read about became part of my life’s experience.

We can’t all hope to write as well as she did—hardly any of us can. But, with work, and the right feedback, deep communication like that is possible for those who try. Communication deep enough to put someone right inside you.

Or, if you don’t want anyone that close, to put your reader inside whatever idea you want them to inhabit for a little bit. It’s an almost magical power. It can do a lot of good.

This is what we aspire to when I work with writers.