Yesterday I completed final revisions on two books, both of them projects I started more than five years ago, in 2019. A feeling of vacancy comes with the departure of these constant life presences. After writing many books, this strange stage of creation is a familiar part of the pattern. And understanding the shape of this natural progression is an important part of being productive as a writer.

In this newsletter I’ll explain how the process works conceptually. In the next, I’ll get into how to structure the mechanics of editing accordingly.

With clients, I often use the analogy of building a house. You start by documenting the family’s needs, then draw plans, and only then get out your tools. You don’t install the drapes before you have finished framing the walls. You avoid having to demolish finished work.

Likewise, writing major pieces.

Big decisions should come first and they should get progressively smaller, until at the end you are deciding between a dash and a semicolon; a decision which hardly matters at all—I should know. That fundamental reality means you should spend more time in the planning stage and sweat the copy editing less.

But that’s the opposite of what many people do, especially non-professionals. Seduced by the feeling of freedom inherent in dreaming up what they want to say, they rush out onto the blank, white page like children going out to play on a snowy morning. Here’s the difference. It really doesn’t matter where a little girl builds her snow fort—it will melt—but your words will stay where you put them until you have to move them later.

Professionals understand this truth, and that’s a major reason we get things done. We start with an idea, scope it out, produce a pitch or proposal, turn that into an outline, and talk over those plans with an editor until we are confident they reflect clear goals and address a defined audience.

Now comes the first draft. When I write, I am constantly reading back, deleting, and rewriting. Nothing matters—I am just playing with clay. I try different tones. I throw away big chunks.

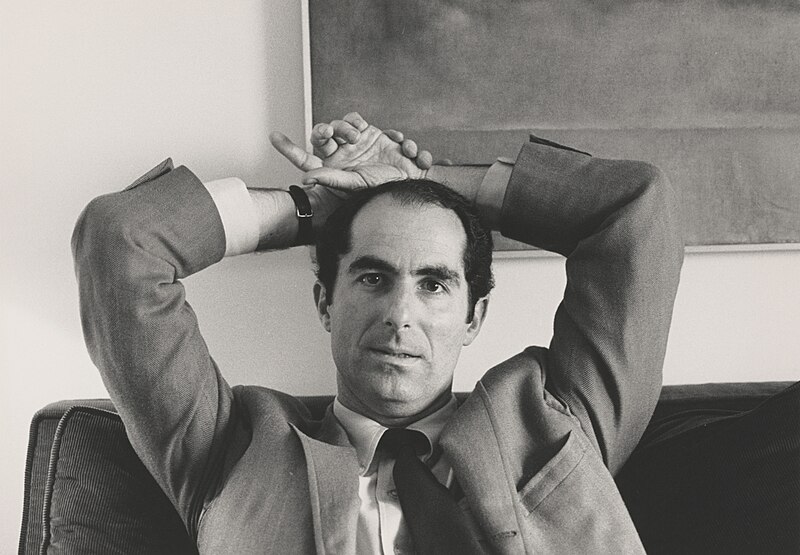

Philip Roth said, “I often have to write a hundred pages or more before there’s a paragraph that’s alive. Okay, I say to myself, that’s your beginning, start there; that’s the first paragraph of the book.”

What’s worse than throwing away a hundred pages? Finishing the whole book before you realize it’s garbage.

Here’s the problem with asking amateurs to read your work. They will proof-read your first draft. If your helper fixes your spelling and grammar at that stage—hanging the drapes in an unfinished house—you are working with the wrong person. Instead, this first editor should tell you if your manuscript functions. If not, what’s broken?

The editing that comes at the end is cosmetic. The undertaker straightening the bowtie before closing the coffin lid.

A writer by then must already be conceiving a new work—bringing a new book to life.

If you enjoy my newsletter, please share it.